One year ago today, an heretic approach to Plan 9’s legacy was born.

I wanted a simple, secure and distributed operating system for programmers.

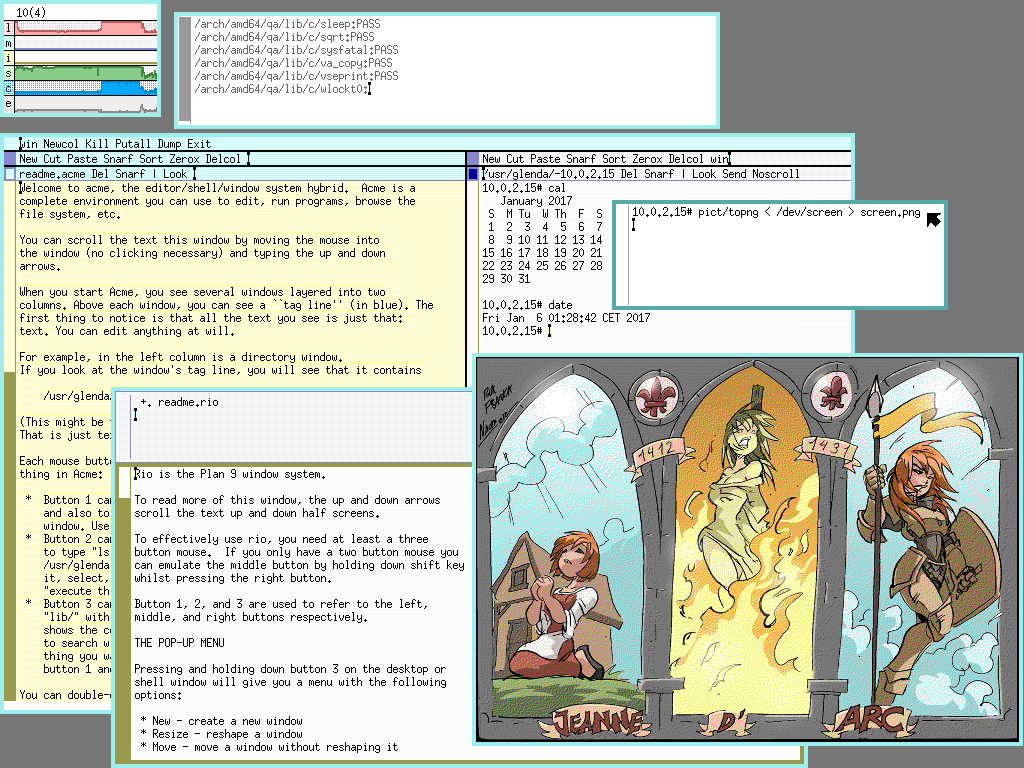

Today Jehanne looks like this:

A lot of work has been done to turn Jehanne from a vision to a runnable starting point, but a little baby cannot be scary!

A pursuit of simplicity

The first goal of Jehanne is to be a simple operating system.

Defining simplicity is hard, but it is a prerequisite for security and usually seems obvious only in retrospect.

As a first step toward this goal I have removed or replaced most of code that Harvey inherited from the Berkeley distribution of Plan 9:

- Jehanne derives its kernel from Charles Forsyth’s Plan9-9k instead of the Nix one imported in Harvey

- it adopts the LP64 programming model (Plan 9 is LLP64 on x86_64)

- many syscalls have been moved to user space or simply removed (and more will go)

- the real-time scheduler has been removed

- the compiler has been outsourced

- most user space tools that are not required for a minimal OS has been removed (as they are going to be distributed as packages)

What remains has been modified in several ways and more drastic changes are coming. However, despite the changes and the removals, Jehanne still inherit most of its code from its noble ancestors.

Major thefts

First, all credit should go to Bell Labs for creating Plan 9 and authorizing the University of California to distribute the 4th version of Plan 9 as GPLv2. While the Jehanne’s kernel comes from a different source, obviously no Plan 9 derivative would exist without the original.

Second I have to thanks Charles Forsyth for his Plan9-9k that rescued me from the “complexities” of Nix and is licensed as GPLv2+. Porting it to GCC has been way easier than fixing Nix memory management (and believe me, I tried really hard!).

Then comes the Harvey’s team that actually let me play with a great project for a while and patiently guided me in the world of OS development. The build tools in Jehanne are evolutions of the Harvey’s original ones and also some userspace tools and a few assembly bits evolved from there.

And I should thanks the 9front developers (particularly Cinap Lenrek and Julius Schmidt) since my rule of thumb is “when in doubt, copy 9front”.

Yes, I know… I should have more doubts! :-D

Their impact on Jehanne is deeper than they might want to admit:

- I ported 9front’s devshr, its usb stack, its awk and several other piece of code to Jehanne

- I choosed hjfs as the default storage in Jehanne and used it to boot Jehanne on real hardware from usb

- whenever I hit a bug in the original code from Plan 9, I check how it has been addressed in 9front

Finally thanks should go to Erik Quanstrom (9atom’s author) and to David du Colombier (9legacy’s maintainer) as they influenced this project in several ways. And obviously, to 9fans, who answer to my crazy questions with their usual humor and wisdom!

So… how did you wasted your time so far?

In 2016 I worked on several aspects of the project, fixing old bugs and adding tons of new ones. It would be impossible to describe each change or decision in a single post. Here you can just find an overview of the largest activities (that I can remember tonight :-D).

Don’t panic!

First I worked on development tools to minimize the cost for newcomers to try and start hacking with Jehanne.

On Debian GNU/Linux you can see Jehanne in action with very few commands:

sudo apt-get install git golang build-essential flex bison qemu-system

git clone https://github.com/JehanneOS/jehanne.git

cd jehanne

git submodule init # we have a lot of submodules

git submodule update --init --recursive --remote

./hacking/devshell.sh # start a shell with appropriate environment

./hacking/continuous-build.sh # to build everything

./hacking/runOver9P.sh # to start the system in QEMU

./hacking/drawterm.sh # in another shell, password: demodemo

The first build will take a while downloading and building the cross-compiling tool chain (GCC, binutils, autotools…), but the following ones will be matter of minutes (or even seconds if you build a single component).

Mess up the kernel

One of the most challenging aspect of Jehanne’s development so far has being cleaning up and modernize the kernel code (and a lot of work is still to be done!).

Now, I know that Plan 9 has been written by programmers that are way better than me, but hey! Jehanne has to be heretic!

To my untrained eye, the Plan 9 design is great, but the actual implementation sucks in several places. And that’s fine: Plan 9 is a research operating system! Indeed you can find in Jehanne warnings like “needs a massive rewrite” that were inherited from the Bell Lab’s code and that will stay untouched for a while.

But to me, the main issue is that the various components are tightly coupled. Very tightly coupled. Since we are going to port several useful unix tools to Jehanne, decoupling will be a leitmotif of its development.

A first example was _tos (top of stack) that coupled the kernel, the profiling machinery and libc. In Jehanne all this is gone: when we will have a profiler, it will be served as a filesystem.

A more subtle example is how Plan 9’s system API is coupled with 9P: for example open()’s mode constants (OREAD, OWRITE…) are the same in libc.h and in the protocol.

To allow new protocols to be integrated in Jehanne as deeply as 9P, I moved all 9P related defines from libc.h to 9P2000.h, I defined new constants (NP_OREAD, NP_OWRITE…) and changed the values in libc.h. It has been a nightmare, but now I will be able to experiment with new protocols way easier.

Finally I renamed devmnt as dev9p to clarify that 9P2000 will be only one among the protocols supported.

To enhance their encapsulation, I rewrote the modules related to the userspace memory. After that, debugging memory-related issues with gdb turned way easier. Several other areas require similar efforts but they have lower priority.

Finally I removed the real-time scheduler. It was not that bad, but frankly when I need a real time OS I use QNX, and its presence was actually imposing an higher complexity to other areas of the system (for example devproc and semaphores).

Shrink its surface

An obvious requirement of an operating system striving for simplicity is to have a minimum number of orthogonal system calls, so that the user space tools and the kernel can evolve independently.

As previously stated, I moved to libc several syscalls (and more are going to be moved in the near future). Some of them are implemented with files from classic devices (eg dup or nsec). For others, like chdir, brk and pipe, a new device called devself has been introduced. Some syscalls have changed their semantics or their behaviour, like open, create and rendezvous. Others have been simply removed, as sleep, stat, wstat and sysr1. The most fortunate one, alarm, is waiting to be turned to a file server from day one, but stay untouched in kernel because of lack of time.

This is still a work in progress and I’m not sure about what will be the final number of syscalls in the system (or even their signatures). Fortunately it doesn’t matter: what I want is a clean and simple system API, free from backward compatibility issues but still able to support modern software.

Indeed I even added a new system call, awake, that deserves a separate post as an iconic example of how a well designed API can both simplify and empower the system.

Poison traditions

One of the first and most heretic decision I made has been to rethink the default namespace organization (aka filesystem hierarchy standard in Linux’s parlance).

Now, I know that with bind and mount you can shape your namespace as you like. I know, Plan 9 is not Unix!

But think of /bin: when UNIX was born most programs were binaries, but now? We have plenty of scripts there! Thus, in Jehanne, all programs are in /cmd.

There is no technical reason for this change, but why should we stick to obsolete names and conventions when we can change them for the better? When you realize this, many other changes arise. The default namespace should minimize name collision to ease navigation. It should be coherent and intuitive.

Again, the current shape of the default namespace shows just a first exploration in the solution’s space, it could change in the future, but I wanted to break it so that we can make it better.

What now?

Now we have a starting point. Small and full of bugs, but it runs on real hardware.

What Jehanne is going to become is up to us.

We don’t need it: Linux, BSDs and Windows are out there and we can use them for fun and profit.

Nevertheless I want it.

I want a system designed for this century.

A clean, coherent and secure operating system.

A system for which I don’t need browsers to host apps.

It might well be just a daydream, but my nightly journey continues.